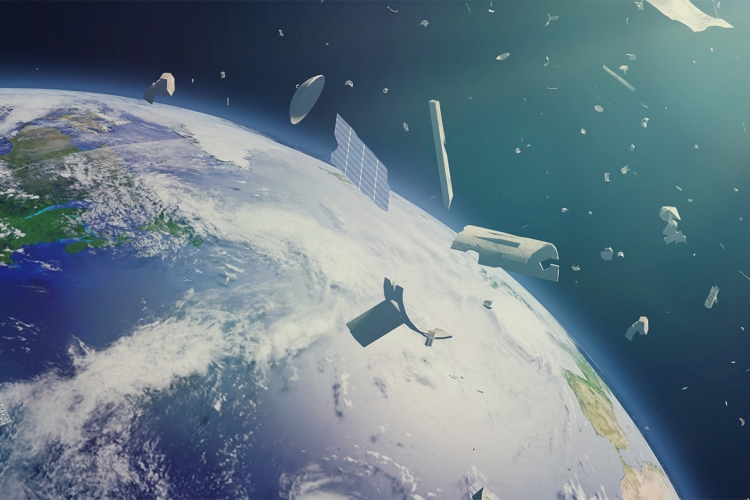

The launch of Sputnik on Oct. 4, 1957, marked the beginning of an intense space race that led to decades of rocket and satellite launches, which eventually resulted in a large amount of space debris. Space debris is anything in orbit that is man-made and is no longer in use. It consists of old, inactive satellites; rocket stages; and other discarded hardware. Smaller pieces of space debris include fragments of vehicles that exploded or collided and bits of insulation and paint that have come off of space vehicles. Generally, the smaller the debris, the more there is of it. This abundance of debris created the need for a military space surveillance to maintain a catalog of all Earth-orbiting objects — active payloads, satellites and debris — along with detailed information about trajectory and point of origin.

This “space object catalog” or Satellite Catalog (SATCAT) is maintained by Joint Combined Space Operations Center (CSpOC) at Vandenberg Air Force Base, part of U.S. Strategic Command. One of the missions of CSpOC is to detect, track and identify all objects in Earth orbit in addition to monitoring the International Space Station (ISS) and other NASA satellites for collisions. Also located at Vandenberg Air Force Base is the The U.S. Air Force’s 18th Space Control Squadron, which operates the Space Surveillance Network (SSN), which oversees radar and optical sensors at various sites around the world. These sensors observe and track objects that are larger than a softball in low Earth orbit (LEO) and basketball-sized objects or larger, in higher, geosynchronous orbits. The sensors can determine which orbit the objects are in, and that information is used to predict close approaches, reentries and the probability of a collision.

As a world leader in space debris research, The Aerospace Corporation (Aerospace) has supported the Space Surveillance Network for nearly 60 years. Aerospace helps the U.S. government estimate the amount of debris created in a collision or explosion, assists with reentry predictions and reentry casualty expectation and is renowned in space traffic management research.

The Problem of Space Debris

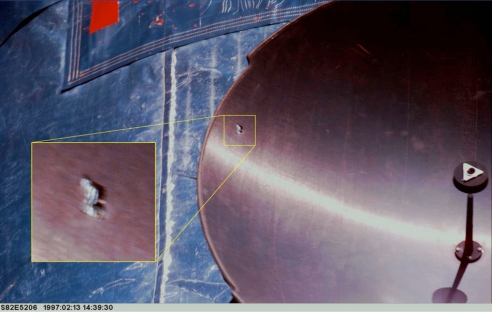

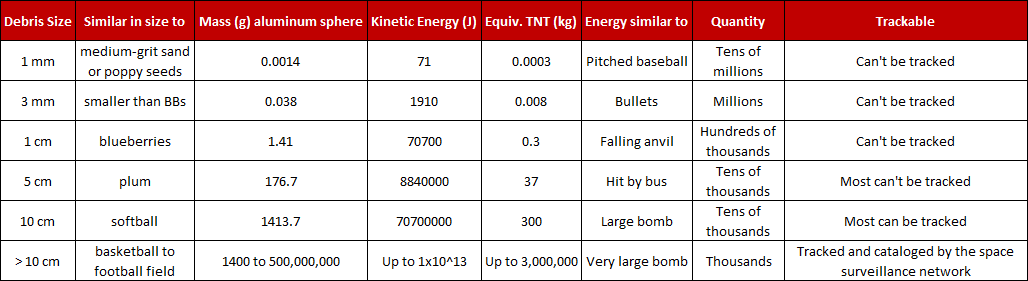

Space debris affects everyone especially since almost everything we do in our modern way of life uses satellite technology. Space debris adds to the cost of operating satellites because if debris destroys a satellite, it may take years and hundreds of millions of dollars to restore that satellite's service. Even tiny debris objects can inflict grave harm to critical sensors and spacecraft components. A one-centimeter-sized object is considered lethal if it hits a satellite and an object down to one millimeter can critically damage a satellite if it hits a critical component. In addition, the growth in space debris will make orbit operations and space flight more hazardous, difficult and more costly if frequent maneuvers are required to avoid debris. A satellite would have to carry extra fuel for these extra maneuvers and would likely need to shield critical areas from collisions with small debris.

The U.S. military is currently tracking about 20,000 objects and has cataloged more than 40,000 objects over the years. Space debris numbers are estimated to rise to over 100,000 objects in the coming years. Most space debris objects are too small to be tracked but large enough to damage spacecraft. It is estimated that there are hundreds of thousands of objects that could be fatal or catastrophic to a space mission and millions of objects that are capable of causing damage.

Complications of Space Debris Removal

Unfortunately, we can’t just vacuum or sweep up space debris into a space garbage truck. To remove space debris, particularly the large and more dangerous objects, we have to get close to it and maintain the same speed as each object. We then must somehow attach to it, and move it into a lower orbit or reenter it directly into the atmosphere, where it will burn up upon reentry. If the object is a rocket stage with propellant still on board, there is an explosion risk, which is why astronauts never perform this task.

There is also the issue of property rights; you can’t grab a satellite or rocket that belongs to another country without their permission. There is no easy way to control the small-but-dangerous objects that are not well tracked or not tracked at all. They have more kinetic energy than bullets, and they are moving ten times faster. It is hard to catch a bullet, especially if you don’t want to create more junk while doing it.

Increased space debris traffic also equals increased collision risk for launch vehicles and satellites on orbit. If the SSN predicts a collision between a cataloged object and a known operational satellite, they usually attempt to notify the owner/operator. Debris can’t be moved, but if the other object is a maneuverable satellite, the object may be able to move out of the way in time to avoid a collision. Most satellite operators require hours or days to plan and execute a collision avoidance maneuver. Other nations use CSpOC data as well as their own tracking data to protect their satellites. Therefore, high-accuracy assessment and prediction tools are essential for reducing risk to current systems and future launches.

CORDS Leads Space Traffic Management

Aerospace’s Center for Orbital and Reentry Debris Studies (CORDS) is addressing the issue of space debris and space traffic management by developing tools and techniques that will analyze potential collision scenarios, study reentry breakups of upper stages and spacecraft and model debris objects in space. These efforts are critical given the predicted population growth in launch efforts and LEO satellite constellations.

CORDS-developed tools encompass a vast array of operations, from predicting possible collisions during launch and on orbit, to predicting hazards to spacecraft after collisions in space, simulating the breakup of reentering debris, estimating the survivability of satellite components reentering Earth’s atmosphere and determining risk to life and property. CORDS provides information on when a reentry might occur, and Aerospace collects and analyses material that survived reentry. This expertise has been used to support the needs of Air Force, NRO, NASA, NOAA, FAA and other customers.

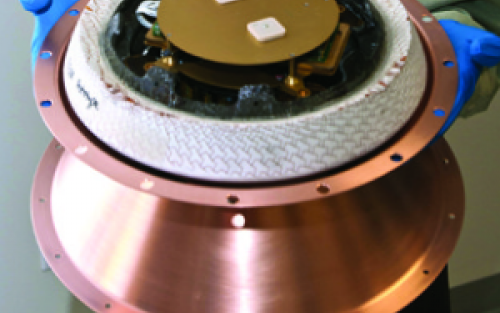

Reentry Breakup Recorder Records Reentry Data

To measure the effects of atmospheric reentry on space objects, CORDS developed the Reentry Breakup Recorder (REBR)—a small, lightweight, self-contained, autonomous, survivable and locatable data-recording device. Attached to a host vehicle, which is generally a spacecraft, this device “sleeps” until the point of atmospheric reentry, when it wakes up to record temperature, acceleration, rotational rate, and other data, including the subsequent breakup of the space hardware due to atmospheric drag, aerodynamic heating, and loads. REBR is released during breakup and protected by its heat shield, survives reentry and “phones home” recorded data via the Iridium system. Five REBR devices have been launched to date, providing innumerable insights into the atmospheric reentry and breakup of spacecraft.

Space Traffic Management Vital for Collision Avoidance

The single most important contribution to managing space debris is to avoid making more debris. Nowadays, satellite operators try to reduce space debris from recently launched satellites and rocket bodies by carefully designing them to prevent explosions, reentering them, or moving them to disposal orbits — essentially a space junkyard — when their mission is over. Another way of preventing space debris is to predict and help prevent catastrophic collisions between existing objects. For nearly two decades, CORDS has pioneered new techniques and processes to provide probability-based analysis for mission assurance launch collision avoidance for all national security space launches. The CORDS team has worked to improve the accuracy of the space object catalog and how to apply this knowledge to achieve effective collision avoidance. Aerospace’s Debris Analysis Response Team provides realtime debris risk assessment for on-orbit collisions and breakups.

The Importance of Space Debris Management

In their efforts to get to the moon, the first space pioneers probably never imagined that space debris and protecting our space environment would ever be an issue. Nevertheless, this is the situation in which space operators today live. There are international guidelines for getting rid of old satellites and rockets from the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC). The problem is that it can be difficult and expensive to eliminate old spacecraft, especially if the satellite or rocket was not designed for disposal. Furthermore, having satellites and rockets dispose of themselves will not work for objects that are already in orbit and are uncontrollable. Therefore, the work of CORDS, along with a robust Space Surveillance Network and the space situational awareness that it enables, are the cornerstones to ensuring a safe operational space environment for future generations.