Update: Launch successful! Stay tuned for more news and updates from the team.

The launch of the very first DiskSat is approaching, and the team behind this versatile new satellite form factor is excited to see it take flight on a Rocket Lab Electron at 9 PM pacific December 17. The demonstration mission aims to show how the pizza-like shape could improve maneuverability, accelerate testing and design, and enable more efficient deployment of large constellations.

"The whole genesis of this was, 'Hey, we want to populate a constellation on orbit with many satellites, quickly and cheaply.' And with this form factor you can stack up a whole bunch of these into a launch vehicle and launch them all at the same time," said Aerospace's Catherine Venturini, principal investigator on the DiskSat project.

In other words, more satellites per launch means fewer launches — or a bigger constellation for the same launch cost. DiskSat is flat for more reasons than launch efficiency, though.

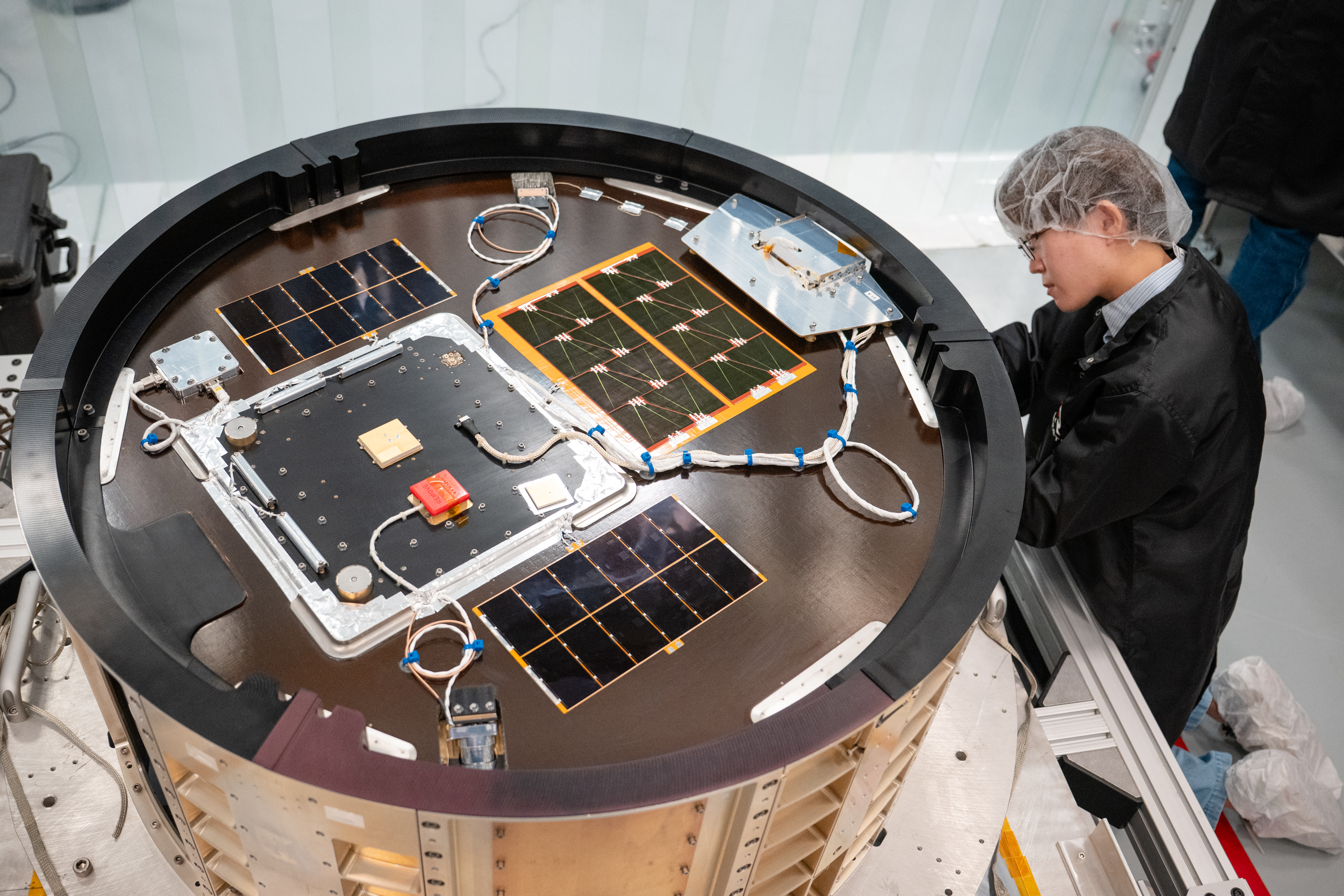

"Most satellites are boxes. Like, a CubeSat is a small rectangular box, and inside, its volume is really packed, so it's hard when you're testing to get in there and replace a board or something," Venturini explained. "DiskSat is just a different form factor than what's out there -- something like a pizza size and shape, right?" (Her family calls it "the pizza satellite," she added).

"So all your electronics are laid out flat, side by side. From a testing and assembly point of view that is really enabling, because it's so much easier to get in and make changes."

Another advantage the shape brings is reduced drag. A box, no matter which way you turn it, usually still presents a considerable surface area to the remnants of atmosphere that degrade low orbits — and that's without reckoning with the sail-like solar panels many spacecraft unfold after deployment. But DiskSat's solar panels are integrated with its surface, and side-on it presents a much smaller silhouette and, theoretically, far greater maneuverability.

"When we get down to VLEO [very low Earth orbit] — this is below 350 kilometers — it's a lot of drag and other elements that you have to overcome. Because of the shape of DiskSat, we can change its orientation so that it has a very low drag profile. The goal being that, with electric propulsion, we can sustain a VLEO for a certain amount of time, which would be very compelling for a lot of our customers and their mission interests," Venturini said.

As a demonstration mission, DiskSat is intended to be the first of many such satellites, Aerospace-made and otherwise. As is often the case, these proof of concept missions are intended to derisk a new approach so that the rest of the space industry can adopt it with confidence.

"Something our customers who are funding the mission were very, very keen on is making this technology readily available for industry to adopt it and build it themselves. There's a lot of missions in comms, PNT [position, navigation, and timing], space weather, remote sensing... from a commercial perspective, for anyone wanting to do constellations, this is very compelling," said Venturini. "We're talking to a lot of people externally who are like, 'we'll wait and see how they do.' Our big push is to not only develop this technology, but demonstrate it. And then they're going to be calling us up."

You can learn more about the DiskSat project here; this launch window opens December 17 at 9 PM Pacific but may change.